Posted 01/16/13

How did the Habsburgs manage forest in the Carpathians? Where were the most fertile soils in the Empire? Or the old-growth forests during Socialist rule? Did the European Union homogenize land uses? Catalina is working on puzzling together the past land uses of the Carpathian Basin and deriving the main land use patterns for the region. She finds that agricultural abandonment and forest cover increase dominate the area, as a result of economic and socio-demographic processes.

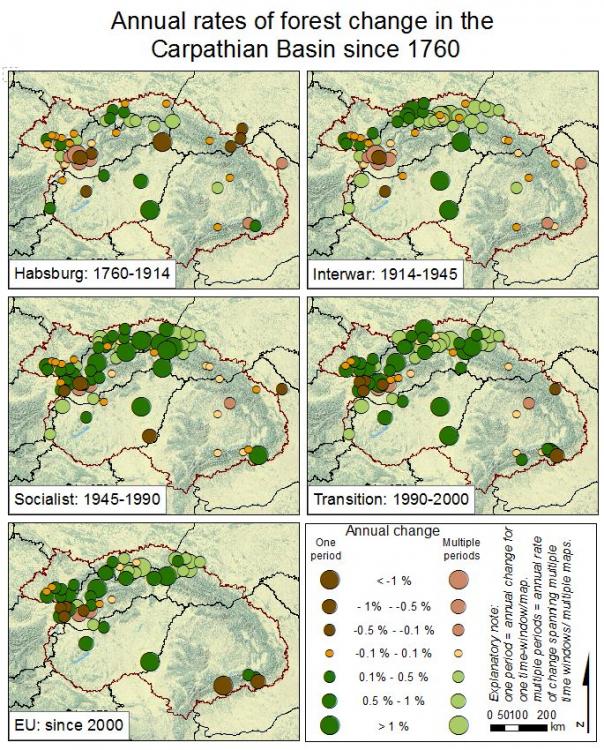

It’s hard to figure out where to go if you don’t know where you’ve been.’ This is a key problem in the Carpathian basin, an area that is within 7 countries and is three times the size of Wisconsin. The region is a European biodiversity hotspot, with the largest contiguous forest in Europe, along with large populations of species of major conservation concern – European bison and brown bears included. The region has also undergone major socioeconomic and political changes over the last three centuries: the rise and fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, two world wars, the fall of the Iron Curtain, and, most recently, the accession of entrance of most of these countries into the European Union. The question at hand is how have these dramatic changes in the human landscape shaped the forests and lowlands that we see today, and what are the implications of these land use legacies for future conservation and land-use planning efforts. To answer this question, Catalina is unearthing untold numbers of dusty and not-so-dusty studies of changing landcover in the Carpathians. Her goal is to piece together the many studies that have been done on small areas across the region over the last 300 years to understand the broader picture of regional land use change. Her findings to date: the growth of the Austro-Hungarian Empire corresponded with a period dominated by deforestation and agricultural development to fuel the growth of the empire and the industrial revolution, while landcover was relatively stable between the two world wars. Socialism brought in a period of strong forest management, while the fall of socialism fostered an increase in forest cover as agricultural fields were abandoned.

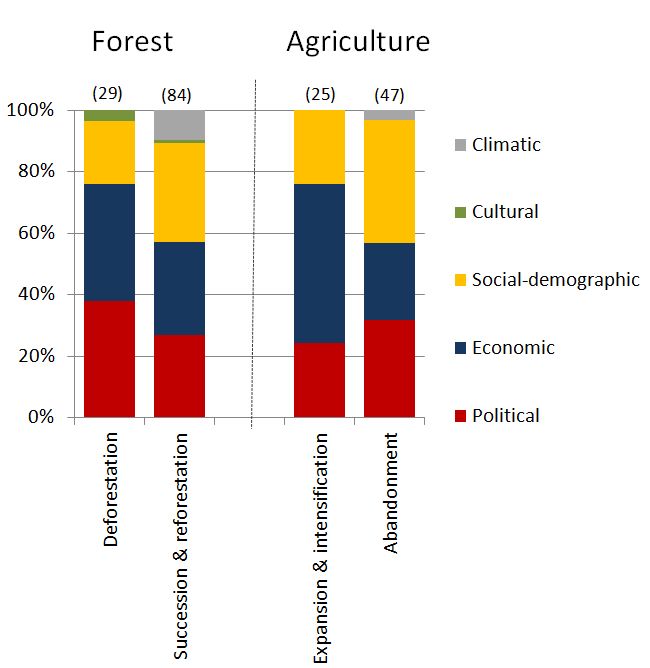

And then there is the second question: what were the drivers of these environmental changes that occurred on the landscape? Were political and socio-demographic upheavals major factors, or were they overshadowed by economics?

Or were climatic and cultural changes a driving force? So far, it appears that early deforestation and agricultural expansion were driven largely by political and economic factors, while agricultural abandonment after the fall of Iron Curtain was driven by socio-demographic factors.Understanding the socio-political happenings that accompanied major land use changes can help us better understand today’s landscape. Are the forests that we see today the product of changes within the last 50 years, or events that occurred 300 years ago? And as a result, where will we have the most success in trying to restore forest or grassland habitats, and where are local hotspots of biodiversity most likely to persist? Catalina’s work will provide the broad-scale, long-term information needed to begin answering these questions, and providing a solid foundation from which to move forward with conservation initiatives to plan for and protect critical areas within this European biodiversity hotspot. However, there is a bit of a hitch. People tend to study interesting and dramatic events. Thus Catalina’s meta-analysis may highlight key peaks and valleys of change, but potentially miss some of the more gradual, longer term changes in the middle of those peaks. Stay tuned for a future chapter in which she’ll address this issue as well!

“

Story by Sarah Carter