Posted 07/15/10

Progressive similarity - the change in community similarity over time compared to a baseline period - is a broad measure of how community similarity changes over time. Using data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey from 1985-2006, and Landsat satellite imagery, progressive change was measured in forests across the conterminous United States. Overall, significant divergence from the baseline similarity for all forest birds was detected from 1986-2005. These large changes in progressive similarity were the result of the combination of small changes in species richness and modest losses in abundance. Forest disturbance increased progressive similarity in Neotropical migrants, permanent residents, ground nesting and cavity nesting species. The highest progressive similarity occurred in the eastern United States.

Bumper stickers usually inspire a brief laugh (or groan). In Chad Rittenhouse PhD, however, the ‘is this the change you wanted? bumper sticker inspired an innovative line of research. The words of the bumper sticker – if not the intended message – motivated Dr. Rittenhouse to question how we perceive change in the natural world, and how our perception of change influences our understanding of nature, and eventually, informs conservation policy. The question became not ‘Is this the change you wanted?’, but rather ‘Is there any change at all, and if so how can we measure it?’

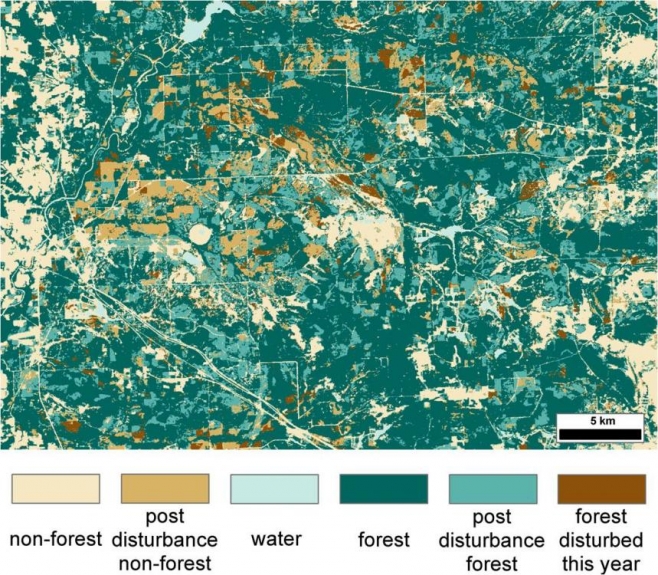

Dr. Rittenhouse set about answering these questions by investigating changes in bird community similarity over a 22 year time frame. Most previous work involving avian community similarity investigated successive similarity (i.e., the change in community similarity from one year to the next). Dr. Rittenhouse, on the other hand, proposed investigating ‘progressive similarity’, the change in community similarity over time, compared to a baseline period. While successive similarity provides a snapshot of instantaneous change, it does not reveal changes in community similarity that take place over longer periods of time. By measuring progressive similarity, Dr. Rittenhouse hoped to capture the changes in community similarity that occur at a slower pace, but that may act as a ‘canary in the coal mine; broadly indicative of deteriorating habitat conditions for all birds.Data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey from the years 1985-2006 was used to quantify avian species richness across the United States. Habitat quality and habitat change are hypothesized to affect community similarity, so data on forest disturbance (derived from Landsat satellite imagery) was used to test the effect of habitat change on community similarity. Because species with similar behavioral traits often respond similarly to forest change, species were grouped into guilds based on migratory habit and nest location, and the analysis was conducted at the guild level. A mixed effects model was used to estimate the effects of forest change, latitude and longitude, on community similarity of each guild.

Overall, Dr. Rittenhouse documented significant divergence from the baseline similarity for all birds regardless of migratory habit and nest location. These large changes in progressive similarity were the result of small changes in species richness and modest losses in abundance. Where forest disturbance levels were relatively high, they were associated with high progressive similarity in Neotropical migrants, permanent residents, ground nesting and cavity nesting species. The highest progressive similarity occurred in the eastern United States.While Dr. Rittenhouse’s findings are interesting in themselves, they are even more important in the context of how ecological change is usually quantified. Using only the measure successive change, which indicated small year-to-year changes, would have provided a false sense of stability in a system that was truly in a constant state of change, as evidenced by the large progressive change. Only by looking at progressive similarity was Dr. Rittenhouse able to discover that communities had changed significantly over the last 22 years.From a conservation point of view, Dr. Rittenhouse argues that the large progressive change is not inherently ‘good or bad, just different.’ The changes do indicate a ‘shifting baseline’ of sorts, and raise questions about what baselines are relevant for ecological analysis, and at what time scales ecological change takes place. These are basic ecological questions that will likely be left unanswered in the near future, or at least until Dr. Rittenhouse is inspired to pursue this question by the right bumper sticker.”

Story by Van Butsic