Posted 01/28/16

Communities that are located in the zone between densely settled urban areas and sparsely populated wildlands are increasingly at threat from wildfires. These fires cause billions in firefighting costs, property loss and can sometimes be deadly. While conventional wisdom holds that rebuilding is inevitable following a fire, SILVIS researchers lead by Patricia Alexandre, have found that rebuilding rates are overall low but that there is also quite a bit of new construction after fires complicating the picture.

People enjoy building houses in beautiful places where they are surrounded by the beauty of nature. Unfortunately, when wildfires rage through forests, these homes are often caught in the fire’s path. As more and more people attempt to enjoy the amenities of building a home in sparsely populated areas, communities increasingly face tough decisions whether to pay for protecting these homes from wildfires that destroy property and take lives. Wildfire costs are not trivial. During the twelve-years from 1999-2011, an average of 1,354 houses were destroyed and approximately $2 billion was spent fighting wildfires, annually. Ideally, communities would have information to help predict how wildfires spread and how to minimize the number of houses lost during wildfires. Unfortunately, a lot of basic information about what happens to a community after a wildfire rips though it is unknown. Patricia Alexandre and her colleagues recently published a study that makes a first step towards describing what happens to communities across the country following wildfire events. While their results suggest that the conventional wisdom that rebuilding always happens has little support and how much is rebuilt varies across the country, they were surprised to find that new housing constructed in burned areas was happening at higher rates than rebuilding, and often at higher rates than in surrounding non-fire areas, adding complexity to the discussion.

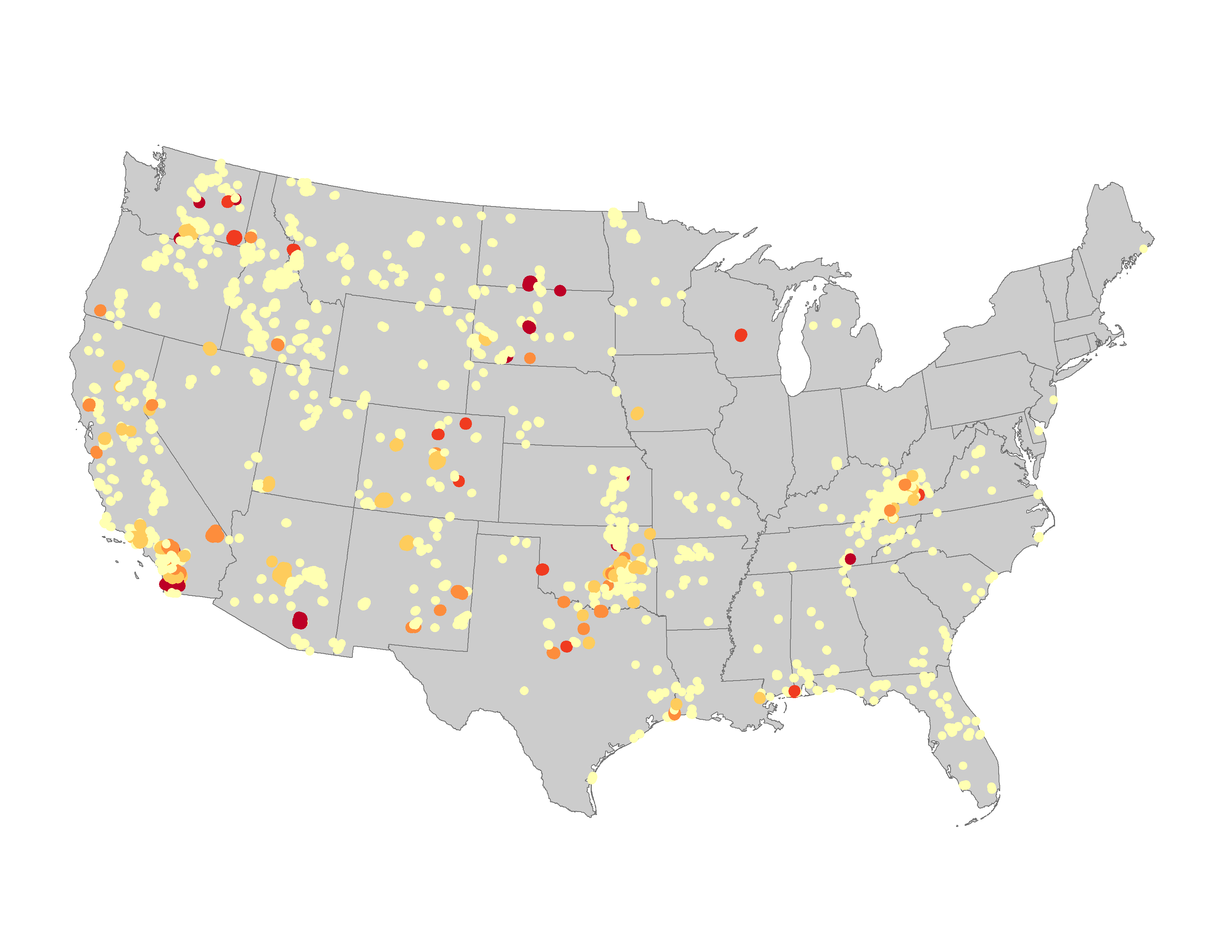

To be clear, Alexandre’s research is not intended to answer whether people should rebuild following a wildfire, but to provide a snapshot of what the patterns were within affected communities across the country following recent fires. This is an important step to take to see whether patterns are consistent across a large scale and provides a dataset to begin drawing conclusions from observed rebuilding patterns. To do this work, Alexandre refined a method utilizing historical images available on Google Earth and then recruited help from students to go through and hand-digitize structures present before a fire as well as all structures that had burned, and consequently been rebuilt within five years following a fire. Nationally, the team found rebuilding rates averaged 25%, with much higher rates in the western states. For example, rates in California approached 70% of structures rebuilt following a fire. The surprising results from Alexandre’s work is first that not all burned communities are re-building within five years following a fire, and second that new buildings were constructed in burned areas at similar or even higher rates. These results indicate that communities are not just replacing homes lost to wildfires, but many are putting new homes into burned areas.

Alexandre offers multiple reasons that homeowners may build, and rebuild, in burned areas, which are inherently fire prone. One reason is that homeowners may find the value they get from living in fire-prone areas worth the fire risk, some insurance policies require rebuilding in the same spot following a fire, and many homeowners do not have the finances to relocate to an area with lower fire risk. While the reasons to build and rebuild in fire prone areas likely vary widely across the country, Alexandre’s research provides a valuable baseline to evaluate future policies or practices that communities might use to mitigate wildfire damages. Whether it’s mandating that new or rebuilt structures be constructed with safer materials, or prohibiting rebuilding in burned areas, the best way to evaluate the efficacy of these policies is to compare them to the housing patterns before and after fire events. Alexandre’s research allows that comparison to take place and hopefully inform local initiatives that could save property, money and lives.”

Story by James Burnham