Posted 08/9/10

A study of forests of the Baraboo Hills, south-central Wisconsin, including Devil's Lake State Park, reveals conservation impacts of >1 million visitors on forest songbirds. While the majority of bird nests were near the busiest trails (88 of 129 nests), daily survival rates were up to 20 % lower near busy trails than near quiet trails. In addition to the human activity, trail width emerged as a key factor in the relationship between recreation and conservation in protected areas.

By design and intent, parks in the United States are areas set aside to conserve biodiversity, natural resources, or culturally significant locations. With an expanding human population, strong interest in outdoor activities, and affordable transportation, it comes as no surprise that state and national parks receive hundreds of millions of visitors each year. Yet, the impacts on biodiversity of park visitors and the infrastructure that supports them are often overlooked. Marty Pfeiffer shed some light on the impacts of recreation trails on birds in the crown jewel of Wisconsin’s Parks: Devil’s Lake State Park.

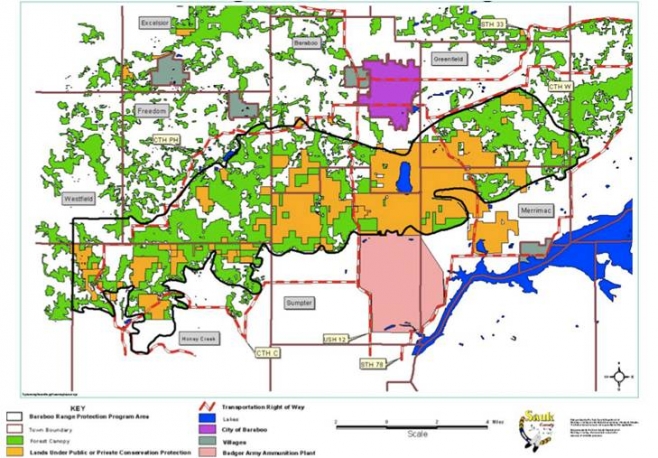

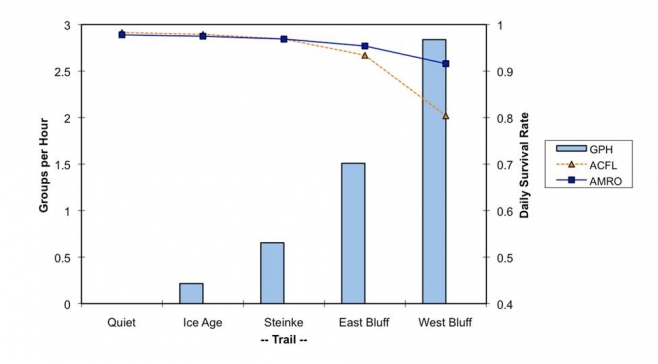

Devil’s Lake State Park, located in the Baraboo Hills of south-central Wisconsin, hosts between 1.2 and 1.4 million visitors every year. The 10,000 acre park contains more than 29 miles of recreation trails that traverse the predominantly forested landscape. In this setting, Marty identified 16 study plots, 8 each on busy and quiet trails. Each study plot was 400 m wide and 200 m long, bisected along its length by a trail. Within these plots Marty searched for and monitored nests of four focal bird species: Acadian Flycatcher, American Robin, Rose-breasted Grosbeak, and Wood Thrush. He also counted the number of individuals and groups of people using the trails while searching for and monitoring nests. Finally, he measured key attributes of the trails and the vegetation around them: trail width at ground level, trail width at 1.3 m above ground, canopy cover, and tree basal area.

Marty found the majority of nests, of the four species combined, near the busiest trails (88 of 129 nests), but those nests didn’t fare as well as nests near quiet trails. In fact, daily survival rate of Acadian Flycatcher nests near the two busiest trails was nearly 20 % lower than near quiet trails. Why are birds using the busiest trails despite the lower nest success? Marty points to the trail, or more specifically, trail width as a potential factor. The busiest trails were also the widest trails. In the contiguous forest of Devil’s Lake State Park, the wider trails may function as canopy gaps, allowing sunlight to reach beneath the forest canopy and increase the volume of vegetation or the number of layers of vegetation. The dense foliage near trails may be appealing to birds seeking refuge from nest predators, or may harbor more invertebrate prey. Yet, human activity on those trails can flush birds off their nests, which may be a factor contributing to increased predation risk. This finding suggests busy trails may function as population sinks – apparent high quality habitat, but with characteristics that cause low nesting success.Does this mean the park should close its trails? Marty is quick to answer ‘No’, but he does suggest that trails could be modified or re-routed in areas of sensitive habitat to provide greater conservation benefits for birds. Marty suggests additional scientific studies are needed as well, to tease apart the relationships between trail width, trail use, and trail location. Such studies, in addition to his, are necessary to build evidence for guiding trail management and trail siting decisions. He hopes that eventually, in part due to data from studies like his, the answer to the new cliche , ‘If they come, can you still conserve biodiversity?’ will be ‘Yes!’

“

Story by Chadwick Rittenhouse