Posted 07/27/11

The Sierra de Manantlan Biosphere Reserve in western Mexico has long been recognized as a hummingbird hotspot. Fire is an important component of the landscape, with the majority set by people to clear land for agriculture. Sarahy Contreras wants to know how fires of varying intensities and frequencies are affecting hummingbird populations in the reserve. Initial results suggest that impacts differ by species, with some species preferring recently burned areas while others remain absent for many years until the pine-oak forest structure returns. Results of the study will inform recommendations for conservation and forest management in the region, and will also provide insight into how hummingbirds may be affected by an increasing presence of fires in western Mexico that current models of global climate change predict.

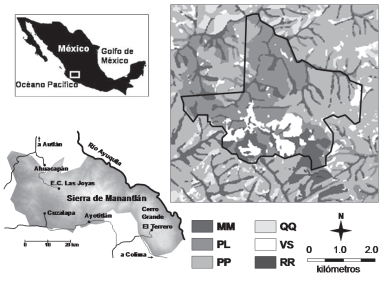

Sarahy Contreras has been studying hummingbirds in western Mexico for nearly 20 years. Her current project tackles the question of how fires, and the anticipated future increase in fires in western Mexico, may affect hummingbirds. Surprisingly, relatively little is known about hummingbirds as a group. Certainly they are hard to study and catch – a tiny bird in constant motion from flower to flower, species to species, and often through continent over the course of a year. Yet this is exactly why. Contreras wants to study them. How are they distributed across the landscape? How closely are their movements linked to the phenology of different flower species? And how do fires of varying intensities and frequencies affect those patterns?The biosphere reserve where Professor Contreras works has long been recognized as a hummingbird hotspot. Of the 24 hummingbird species that occur in the state of Jalisco, 23 of them are found within the Sierra de Manantlan Biosphere Reserve. The reserve sits in the mountainous area of western Mexico, which during the winter harbors the highest diversity and abundance of terrestrial migratory birds throughout the Neotropical region. But the reserve is not just for birds and the pine-oak forests which dominate its landscape. Nearly 400,000 people live within and around the reserve as well.Fire has traditionally been an important component of the landscape in western Mexico and an important tool for its people. The majority of fires are set by people to clear land for agriculture. On occasion, these fires escape and can burn quite large areas. Some of these wildfires are of relatively low intensity, primarily burning the shrub layer and rarely reaching tree crowns. Other fires are severe – burning everything up to and including the tree crowns. A large effort is currently underway in the Sierra de Manantlan Biosphere Reserve to change local attitudes and practices related to fire. Part of this project is an increase in capacity to put out fires once they are started. Another important component of the project is education for the communities inside the biosphere on the natural resources in the reserve and how those resources and species are affected by fires.

Professor Contreras is studying the effects of these fires on hummingbird populations in the reserve. In particular, she is examining how hummingbirds fare over time in sites that were burned by fires of different intensities. Professor Contreras is also interested in how hummingbird populations change over time in previously burned sites. Her study sites include a continuum of sites burned relatively recently (less than 10 years ago) to sites burned more than 25 years ago. As these sites become revegetated and move through various stages of forest succession, Professor Contreras is tracking not only which species are using the sites but also the health of the populations of the individual species. Metrics including abundance, age and sex ratios, and survivorship provide an indication of the health of these populations over time. Luckily Professor Contreras started collecting bird data in the reserve nearly 20 years ago. She initiated and now coordinates a bird banding program that is active both in the biosphere reserve and throughout Mexico. The resulting comprehensive database of bird observations across sites and over time is allowing her to look at population response to burned sites over a 25 year time period – a rare opportunity to understand long term responses of hummingbird populations to fire.

Professor Contreras is just beginning to analyze her data. Initial results suggest that the response of hummingbirds to fire depends on the species in question. For example, rufous hummingbirds, a common visitor to the US and one of the hummingbird species with the longest migrations, do quite well in recently burned areas. However, as burned sites succeed back toward a closed canopy pine-oak forest, their use of sites decreases. In contrast, Amethyst hummingbirds, a resident forest specialist with a very restricted range a preference for pine-oak and cloud forest habitats, are essentially absent from recently burned sites and only return once the forest structure returns.The results of the study will be important for the conservation of hummingbirds, identifying the particular habitats that different species depend on, and how populations of those species respond to the presence of different intensities and frequencies of fire on the landscape. Results will be translated into recommendations for conservation and forest management within the region that may benefit both resident hummingbirds and migratory species which overwinter in the reserve. The study will also provide insight into how hummingbird populations may be affected an increasing presence of fire in western Mexico that current models of global climate change predict.

“

Story by Sarah Carter