Posted 07/28/11

Across the US, hundreds of wildlife refuges protect wildlife habitats, often within human dominated landscapes. Unfortunately, not only wildlife is drawn to these refuges, they also attract humans, who like to build their houses nearby. Chris Hamilton, a former Fish and Wildlife Service employee and now a SILVIS PhD student, found that housing density around refuges has been steadily increasing in the past decades, and consequently these refuges have become more isolated from neighboring natural areas, with potentially detrimental effects.

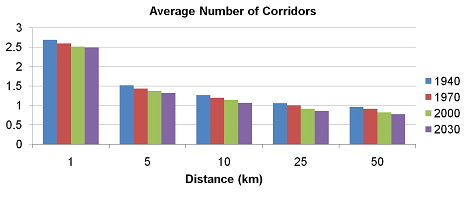

The wildlife refuge system, which dates back to 1903 when Theodore Roosevelt established Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge, is a conservation success. Today, 494 refuges are scattered across the 48 contiguous United States, ranging in size from less than 1 to over 400,000 hectares. The refuges are important to hundreds of bird species for breeding and stopover habitat during migration, as well as to other types of wildlife, from mammals to fish. Many of these refuges are located within human dominated landscapes, surrounded by private lands, and often adjacent to human settlements. However, housing development around refuges does not happen by chance, it turns out that people actually prefer to build their houses near refuges. This pattern occurs for a variety of reasons including better access to nature, increased property values, or the assurance of no development on the neighboring refuge land. Chris claims that we may be ‘loving them to death’. He found that in every decade since the 1960s, the amount and density of housing immediately adjacent to most of the nation’s refuges has increased faster than the national average. The direct outcome of this development, was an increasing isolation of the refuges from neighboring natural areas, as the number and area of undeveloped corridors connecting each refuge and its surrounding landscape decreased through time. style=text-align: center;>

This decrease of connectivity can have detrimental effects on species that need to travel between different natural areas to find food and breed, as their ability to traverse the human dominated landscape outside the refuge is diminished. In addition, the ability of species to move from their current locations to far away habitats has a key role in their ability to adapt to climate change. Blocking their pathways outside their current habitat may doom them when climate conditions slowly change and their current habitat becomes unfavorable. Furthermore, if an isolated refuge is struck by a major disturbance event, like a wildfire, that extirpates a species, there is no way for species from other natural areas to re-colonize it. Beyond the isolation effect, housing development around refuges causes other problems, such as habitat loss, introduction of invasive species, ‘subsidized predators’ such as feral cats, and nutrient flow to the refuge. All of these issues highlight a key challenge in conservation science: protecting a single habitat patch is not sufficient to guarantee its long-term sustainability. Protected areas need to be connected to other natural habitats in ways that can support migration and gene flow between them. style=text-align: center;>

Chris’s findings raise a troubling image of the future of national wildlife refuges. With increased isolation and limited connectivity among natural areas, their effectiveness may decrease. Paradoxically, the very same characteristics that made these refuges such an effective tool for conserving habitat for numerous species may be contributing to their demise. This poses a great challenge for conservation managers, as the planning of future areas for conservation should take into account the potential land use change outside the refuges, and its associated negative consequences.”

Story by Avi Bar Massada