Posted 08/3/11

The Karner blue butterfly is a small butterfly whose lifecycle depends on blue lupine (Lupinus perennis), a characteristic plant of oak savannas. The species has lost the majority of it's habitat in the Midwestern US due to land cover changes after European settlement. Restoration of oak savannas is therefore crucial for survival of Karner blue butterfly. But can we use this opportunity to protect other characteristic savanna species while protecting the butterflies? A SILVIS researcher, Eric Wood, attempted to answer this question investigating savanna bird communities in Western Wisconsin.

The Karner blue butterfly (Lycaeides Melissa sauelis) is classified as a federally endangered species and its major decline is caused by habitat loss mainly because oak savannas have been converted to other land uses, or to forests due to succession. Oak savannas once were widespread throughout the upper Midwest and the Great Lakes region all the way up to New England. Since European settlement though, oak savannas and barrens, which are critical habitat for the Karner blue butterfly, have been converted to other land uses, replaced by development, agriculture and forests. Restoration of oak savannas is therefore essential for survival of this species and many restoration actions are carried out across the upper Midwest to provide habitats for Karner blue butterfly. However, oak savanna is also important habitat for many other species.Thus, it is possible that managing oak savannas for the Karner blue butterfly provides a conservation benefit for bird communities that use this habitat during the breeding season. Eric Wood, a researcher and postdoc in the SILVIS lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, investigated this by examining avian communities in the Karner blue butterfly restored oak savannas at Fort McCoy Military Installation during his PhD study. The topic is especially important because, so far, there are no conservation plans for the birds that use oak savanna for breeding in Wisconsin and thus this study provided an opportunity to better understand how oak savanna habitat restoration impacts bird communities.

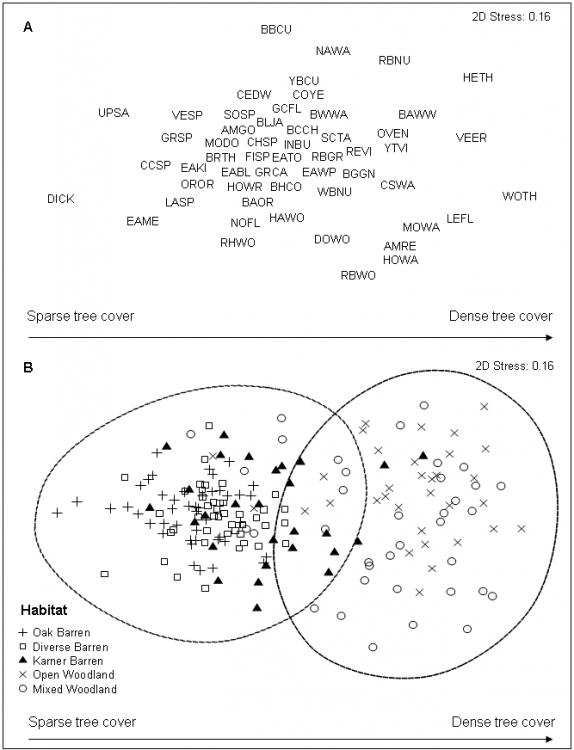

Wood and his team of field technicians surveyed birds in three different ecosystems occurring at Fort McCoy: restored oak savannas, remnant oak savannas, and oak woodlands that were formerly oak savannas but where succession resulted in higher tree density now. Wood observed that bird communities structure is similar between restored and remnant oak savannas. Yet, there is not a perfect overlap of bird communities using the two habitats.According to Wood’s research the main factor which differentiates the bird communities of remnant and restored oak savannas is the surrounding habitat type (i.e., landscape context). This turned out to be more important than time since restoration (i.e., time lags), restoration technique, or patch area size of the restoration. When restored savannas are surrounded by grasslands or remnant oak savannas, bird species characteristic for sparse canopy habitats (e.g., oak savannas) occur in high densities in the newly created habitats. However if restored plots are surrounded by dense woodland or forested ecosystems, dense canopy associated bird species tend to predominate. ‘To protect the Karner blue butterfly and bird communities that use oak savanna habitats, the location of future restoration savanna plots should be chosen carefully, taking into account the context of whole landscape’ says Wood. These results are important for land managers and provide a useful step towards better understanding conservation for bird communities that use oak savanna habitats. style=”text-align:”>

“

Story by Elzbieta Laszczak