Posted 03/31/14

The Black-necked Crane, the only alpine species of crane, has fluctuated in numbers at Yunnan's Napahai wetland. After a rapid decline through the 1980s and a gradual recovery until the early 2000s, the population is less than 300 today. James Burnham and collaborators are trying to understand these trends by combining field observations with high-resolution satellite imagery to link changes in the wetlands of Napahai to the changes in use patterns of Shangri-La's cranes.

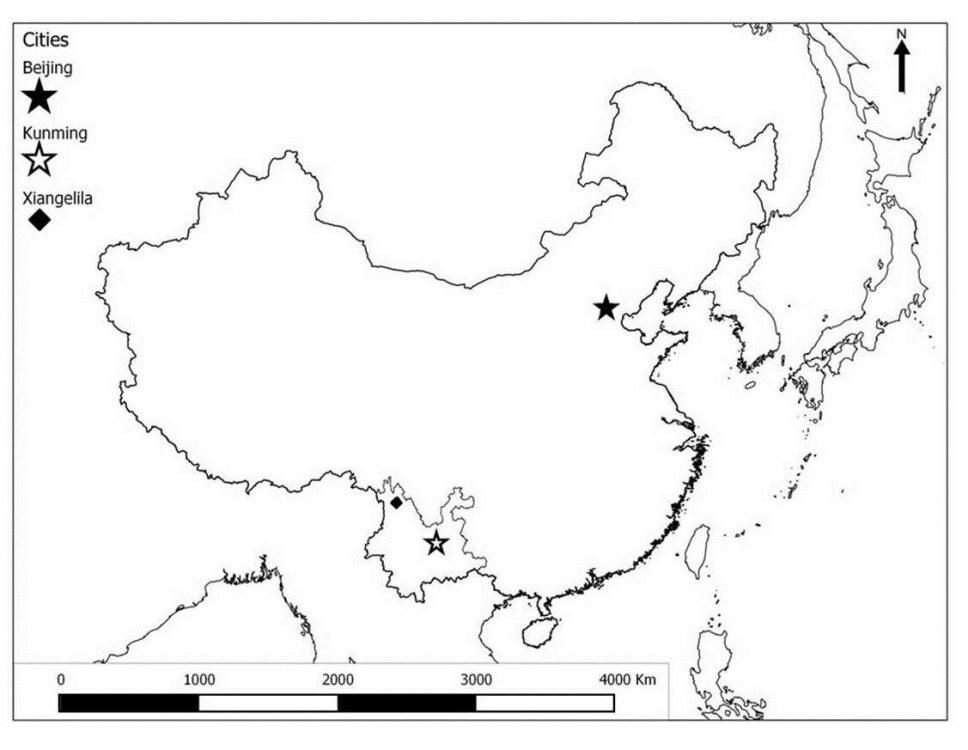

Napahai, a high mountain valley wetland in southwest Yunnan Province, is one of three major wintering areas for the Black-necked Crane. With peak counts of the birds at Napahai totaling almost 1,000 birds in the 1960s, the population declined to less than 100 cranes in the 1980s.

Then, in the early 1980s the creation of water impoundments increased the available habitat for the crane, and the population increased to between 300-500 birds. However, since the mid-1990s, there has been an increase in infrastructure development and agriculture in the valley. While the global population of black-necked cranes has been on the rise over the last 10 years, now estimated at approximately 10,000, the number wintering at Napahai has been steadily declining. Why such a drop in the wintering population? James Burnham along with collaborators from the International Crane Foundation, the Kunming Institute of Zoology, and the University of Strasbourg are trying to find the answer.The reasons for the fluctuating number of Black-necked Cranes observed at Napahai are not straight forward. ‘The expansion of water and agriculture (important foraging and roosting habitat for the cranes) may have helped increase wintering numbers,’ James notes, ‘but further infrastructure development and changing patterns of agriculture may have countered these benefits and reduced Napahai’s utility for wintering Black-necked Cranes.’

The size of the wetland fluctuates based on local precipitation, which changes the areas available for foraging and roosting, but other changes in the landscape are also in play. Napahai sits at the center of northwest Yunnan’s Deqen County with a population of over 130,000 individuals, predominately ethnic Tibetan and Naxi minorities. The county seat of Shangri-La, renamed in 2001 to entice tourists to this picturesque valley, sits at the edge of Napahai and its development has had dramatic impacts on Napahai.James and his colleagues are employing multiple techniques to investigate these patterns. He uses imagery from the SPOT and QuickBird satellites, which capture high resolution (down to 2.5 m pixel size) imagery to provide pictures of the entire wetland, adjacent uplands and the city of Shangri-La.

Based on these images, he is creating highly detailed maps that show the land cover composition of the area. Once those maps are completed, James and his partners will link the observed locations of Black-necked Cranes to these detailed land cover maps and identify which habitats are most important to the birds. James is also attempting to link the fine-scale satellite imagery to Landsat imagery, which does not provide as much detail as the SPOT or Quickbird satellites, but will provide more information about how Napahai has changed since the mid-1980s when economic reforms began to really transform the region. The ultimate goal is to identify how land cover has changed at Napahai, quantify the changes in foraging and roosting habitat and link those patterns with the changes observed in the numbers of Black-necked Cranes wintering in the valley. With that information, James and his colleagues might be able to piece together what is causing the decline in the valley and make concrete recommendations to local resources managers about how to limit, or even reverse, the decline of the cranes of Shangri-La.”

Story by Max Henschell