Posted 01/28/10

Across the upper Midwest, oak forests and savannas are being replaced- by development, agriculture, and by other tree species whose germination does not depend on the fires that once regularly occurred in southern Wisconsin and other states with oak savannas. SILVIS researcher Eric Wood is working to find out how migrating wood warblers might be affected by declines in oak in western Wisconsin. While his field work is on-going, preliminary results indicate that the arrival of some species coincides with oak flowering, suggesting the importance of these trees to warblers.

The forests and savannas of Wisconsin are undergoing tremendous changes, according to Eric Wood, a researcher and graduate student at the SILVIS lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. On one side, there is a warming climate and accompanying changes in phenology (the timing of biological events such as leafing out, flowering, and arthropod emergence), and on another, there are changes in the landscape, such as fire cessation and urbanization. One very visible consequence of these changes is that forests and savannas that were once dominated by oak species are being replaced by red maples, sugar maples, basswood, and other more shade-tolerant species. While this is happening in Wisconsin, a lack of oak regeneration is also occurring in other forests on the western slope of the Appalachians, the upper Midwest, and in the oak woodlands of California. A wide variety of organisms inhabit oak woodland, so it is important to understand how they use oak habitat and what the consequences of its loss might mean for them.Among the most diverse and colorful groups of North American songbirds are the wood-warblers (family: Parulidae), which number some 30 species, of which 15 or so are the long-distance Neotropical migrants that use the woodlands of Wood’s Fort McCoy and Kickapoo Valley Reserve study sites. While most of them breed further North in Canada, they heavily use Wisconsin resources on their journey north. ‘Migration stopover is really understudied by ecologists. We don’t know how different trees are used by migrating birds and how a loss of oaks will affect the migration of birds’ says Wood, a California-born avian ecologist. While warblers that winter elsewhere in the US appear more flexible in their diet, ‘the Neotropical warblers really seem tied to flowering and leaf out events of oaks and other associated trees’, continues Wood.

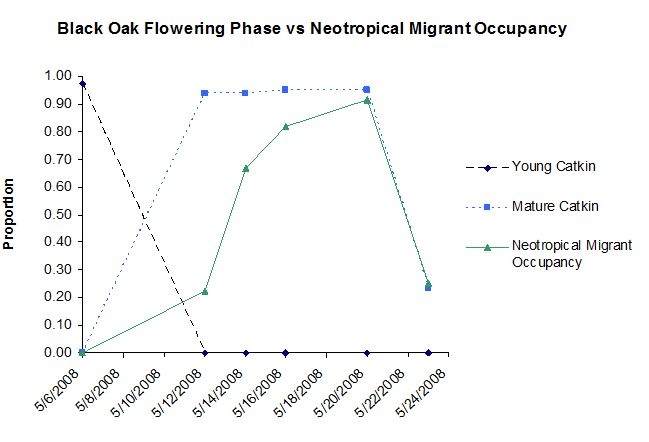

Wood’s team studies foraging behavior of birds in tree oak canopies, comparing their use and success in finding food in different tree species. He also is using wire cages to compare the invertebrate abundance and diversity found in areas of trees where birds are excluded from foraging with areas where they are not. It is challenging and tedious work to sort through, identify, and tally invertebrates from these comparative treatments.Wood has observed a link between oak catkin maturation and the arrival of the migrating wood warblers (Figure). According to Wood, it is unknown what proximate cues warblers responded to when selecting stop-over locations. Many other questions intrigue Wood, who plans to continue warbler research at a broader scale and tie his work to studies of climate change, phenology, and ecosystem services. For example, Wood wonders whether the warblers are providing a valuable service to the oaks be relieving them of the burden of insects that consume their catkins.

“

Story by Thomas Albright