Posted 01/27/10

How important is the past to understand present plant invasions? Gregorio Gavier Pizarro recently made a big step towards answering this question. He found that plant invasions in the Baraboo Hills in Wisconsin depend more on historic housing and road patterns than on today's urban sprawl. To the contrary, contemporary forest fragmentation explained invasions better than fragmentation legacies. Gregorio's work clearly points land managers to account for past housing fighting invasions and planning future development.

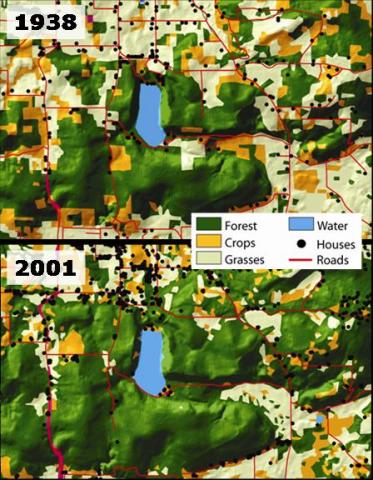

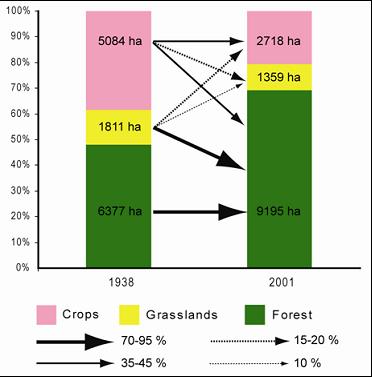

We know that contemporary landscape features such as housing patterns, roads, and forest fragmentation affect the distribution of invasive plants. To test how important past landscape features are in explaining today’s invasions, Gregorio Gavier Pizarro changing landscape features in the Baraboo Hills, Wisconsin between 1938 and 2001. Housing patterns, road density, and forest fragmentation was quantified from historic orthophotos and contemporary land use maps. These landscape features were then compared to the cover and richness of a number of common invasive plants, sampled in 105 plots in the study region in 2007.The results of this comparison clearly showed that historic housing and road patterns strongly influence today’s plant invasions, even more so than housing growth and road development that is ongoing now. On the other hand, contemporary forest fragmentation was more important for explaining plant invasions than historic forest fragmentation. The main conclusion from these results is that the legacies from housing and road development may be much more enduring than legacies from forest fragmentation. Gregorio’s work suggests that different dynamics that characterize these landscape features in the Baraboo Hills explains why they affect contemporary invasions differently. While houses and roads are relatively static and persist for long times in the landscape once they are established, rapid land use change has been the main driver of forest fragmentation in the Baraboo hills during the 20th century. Much farmland has been abandoned after 1938 and forests have expanded in many areas. Thus, former forest edges are now deep inside interior forest, and this may explain why they do not propagate invasions today.

This study considered six different common invasive plant species: Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii), Autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), honeysuckle (Lonicera sp.), common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), and bittersweet nightshade (Solanum dulcamara). Invasive plant species richness was significantly more associated with the 1938 housing and infrastructure patterns than with the 2001 ones. For example, richness depended more strongly on to the number of houses in a 1-km buffer around each plot and to the distance to the closest road in 1938 compared to 2001. While forest fragmentation in 2001 was a better predictor of richness than forest fragmentation in 1938, fragmentation was generally weaker in predicting invasive plant species richness than variables connected to past housing and road patterns.

The cover of invasive plants was also strongly associated with the 1938 human development variables. For example, invasive plant cover depended significantly more on the distance to the closest houses in 1938 than in 2001. Yet, housing and road development legacies affected some invasive plant species (e.g., honeysuckle) more than other (e.g., multiflora rosa or Japanese barberry). Conversely, explaining the variability in cover of those species that were less affected by housing and road pattern legacies depended more strongly on today’s forest fragmentation. Generally though, forest fragmentation, both in 1938 and in 2001, was a weaker predictor of invasive plant cover than housing and road pattern legacies.In explaining these patterns, Gregorio points out that the long-lasting effect of housing and roads development exhibited 70-year ecological legacies that are most likely the effect of past propagule pressure and introduction points. On the other hand, his work showed that forest fragmentation, which is generally believed to provide more suitable habitat for invasives, affected invasive plants much more immediately. These findings have important implications for managing invasive species and for landscape planning. Nature conservation concerned with removing or surprising invasive plants should consider how housing and infrastructure patterns have evolved over time if they want to be successful. And landscape planners should be aware of the possible future plant invasions connected to the housing development decisions they take today.”

Story by Helmers, David