Posted 12/13/18

For the past decade endangered Kirtland’s warblers have been calling red pine dominated plantations in Wisconsin home, due to habitat saturation as a result of population growth in their core range in Michigan. Interestingly, Kirtland’s warblers have only occasionally been known to breed in red pine forests in the past, instead usually only breeding in jack pine forests of a certain age. Ashley Olah is examining the characteristics of these red pine dominated plantations to see how they may differ from the habitat typically used in Michigan for breeding, and the success of Kirtland’s warblers in this novel habitat.

After coming close to extinction by the early 1970s, nearly twenty years ago Kirtland’s Warblers (Setophaga kirtlandii) achieved the population recovery goal set by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and since then have exceeded that goal; stabilizing at nearly twice the population size set as the goal when they were first listed as endangered. The current population estimate is approximately 2300 pairs. Therefore the US Fish and Wildlife Service is in the process of removing Kirtland’s warblers from the Endangered Species List. While reaching this goal is a huge step forward, there may be negative implications of delisting this extremely specialized species, as it will always rely on habitat management for its persistence.

Kirtland’s Warblers are habitat specialists, meaning that they have evolved to use only very specific habitats. Traditionally, Kirtland’s warblers bred in patches of wildfire-regenerated jack pine forest, on sandy soils, and they only used these areas while the trees were young and approximately five to 20 feet tall. Their stronghold has been lower Michigan, where approximately 99% of the population exists. Fire suppression and deforestation associated with European settlement in the Great Lakes region led to major decreases of young jack pine forests, the essential habitat necessary for foraging and nesting by Kirtland’s warblers. While Kirtland’s warblers don’t nest in the jack pine trees themselves, they do make use of the lower branches of the adolescent trees to camouflage and protect the nests, which are located on the ground, often close to the base of a tree. As the jack pines age they shed these low hanging branches and nests not hidden from view are exposed and vulnerable to predation. These low live branches available only in young stands of jack pine seem to be an in important element females use to select the placement of nests.

The decline in young jack pine forests together with nest parasitism by Brown-headed cowbirds led to the decline in Kirtland’s warblers, and their listing on the Endangered Species List. In subsequent management aimed at recovering the species, habitat had to be created by harvesting and planting jack pine in patterns that mimicked the way jack pine grew after wildfires – patches of dense pines with interspersed openings. Management, also including cowbird control, was successful, warbler population size increased, and eventually all suitable habitat in lower Michigan was saturated by breeding Kirtland’s warblers, and some birds began to prospect for new breeding areas outside of their core range.

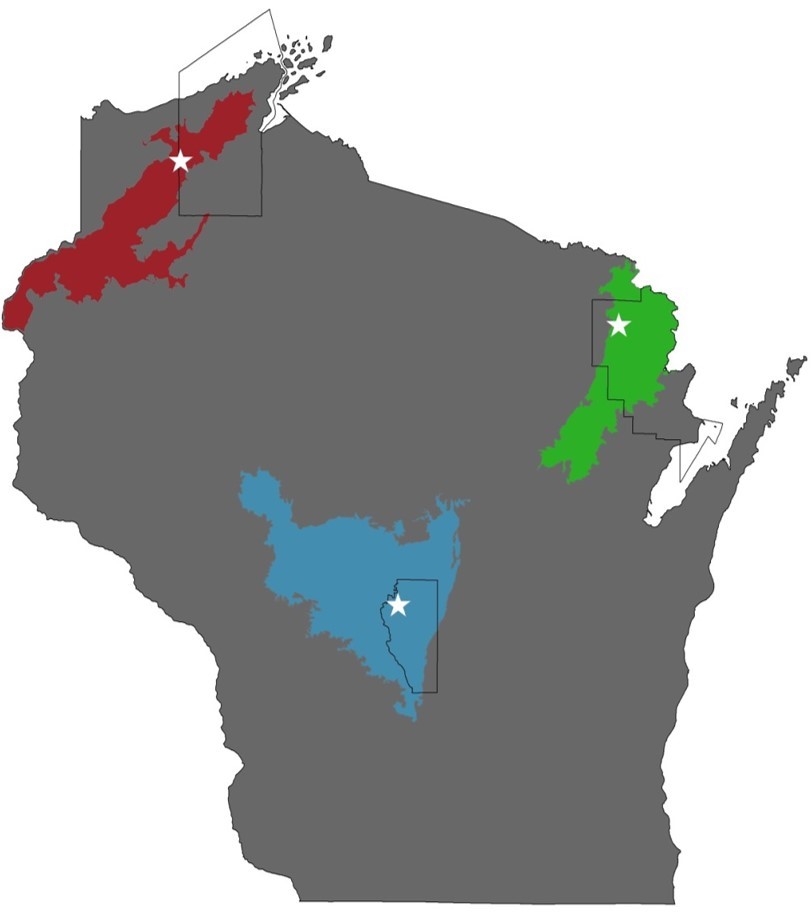

Around 2007, Kirtland’s warblers started to colonize a non-traditionally used habitat, commercially owned red pine plantations in central Wisconsin. Kirtland’s warbler have been breeding in those plantations of young red pine ever since.

The population recovery in Michigan, subsequent prospecting for new breeding areas, and colonization of habitat in Wisconsin is exciting, and is promising news for the long term persistence of the Kirtland’s warbler. When members of a species are spread across different geographic areas, if a disaster strikes one area, the individuals in other areas can still carry on and perhaps serve as a source to repopulate the area where the disaster occurred. While the Wisconsin population is not large enough to buffer the species from a large catastrophic event in the core range in Michigan, this range expansion is a step in the right direction, and researchers and managers in Wisconsin are working to increase the small number here by ensuring that suitable habitat is available.

What is it about red pine plantations that attract Kirtland’s warblers though? Ashley, in collaboration with scientists from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, set out to observe the warblers and collect data about the Wisconsin red pine dominated plantations they breed in to try to find the answer.

Ashley has found that a major factor in Kirtland’s warbler habitat selection is the age of the red pines, which parallels their use of jack pines in Michigan. Red pine saplings are planted at relatively high density, similar to the density of naturally regenerated jack pines that Kirtland’s warblers rely on. Red pines also tend to retain their lowest branches longer than jack pines. This trait of red pines may mean that they can hide nests on the ground in a way that Kirtland’s warblers find suitable, for more years than jack pine do. Additionally red pines thrive on the sandy soils that support jack pine, and that quickly drains after rain events, keeping Kirtland’s warblers’ ground nests dry. A final factor that Kirtland’s warblers seem sensitive to when deciding where to place their nest is litter depth.

Ashley has also found that nest success of Kirtland’s warblers in red pine plantations is comparable to nest success in jack pine.

Ashley continues to study Kirtland’s warblers’ use of red pine dominated forests in Wisconsin. Using data collected from nest cameras and radio transmitters she plans to identify nest predators, learn more about Kirtland’s warblers’ nesting behavior, and to document survival rates of juveniles after they leave the nest at her Adams County, Wisconsin study site.

Story by Kozidis, Sofia